This post is part of a series of interviews that we are conducting with product leaders across various industries. In this interview series, product leaders share their product management lessons and advice with their fellow product managers. We hope this series will shed light on trends and challenges in the profession, and be helpful to new and experienced product managers alike.

The following is a conversation with Brian Crofts, VP of Product at Namely. Namely is a fast-growing, all-in-one HR platform. Before Namely, Brian held a variety of product management and finance roles at Intuit. Here’s Brian’s story.

How did you get into product management?

Brian Crofts (BC): I started my career at Intuit as a corporate finance intern. Like most people, I didn’t go to school for product management. I studied economics and finance and discovered PM later. I considered several career paths after college, but in the end, I chose to stay in finance.

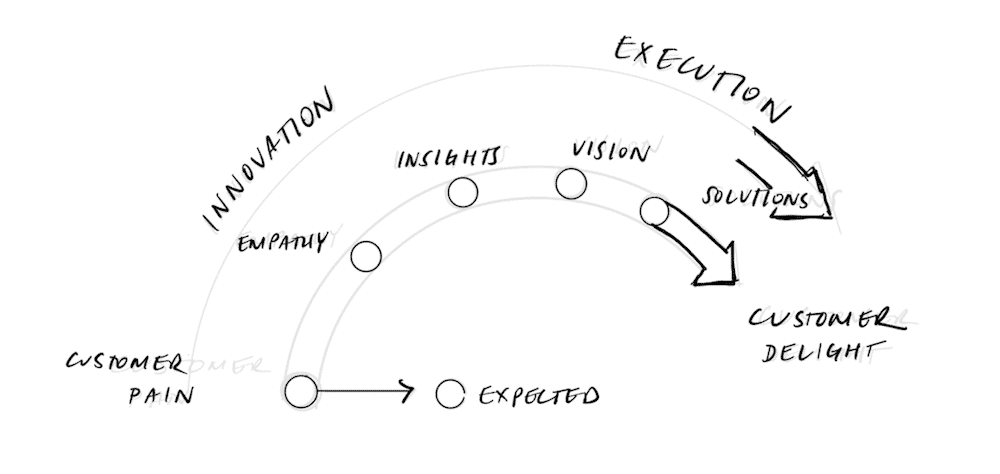

Early on, I saw a product manager on stage at an Intuit all-hands and I thought, “that guy has the best job.” The product manager was a great story teller. He articulated a clear customer problem and had deep empathy for the customer’s pain. He then shared his vision on how to solve that problem, in a compelling way. I knew I wanted a career in product. A year later I was building my first mobile application.

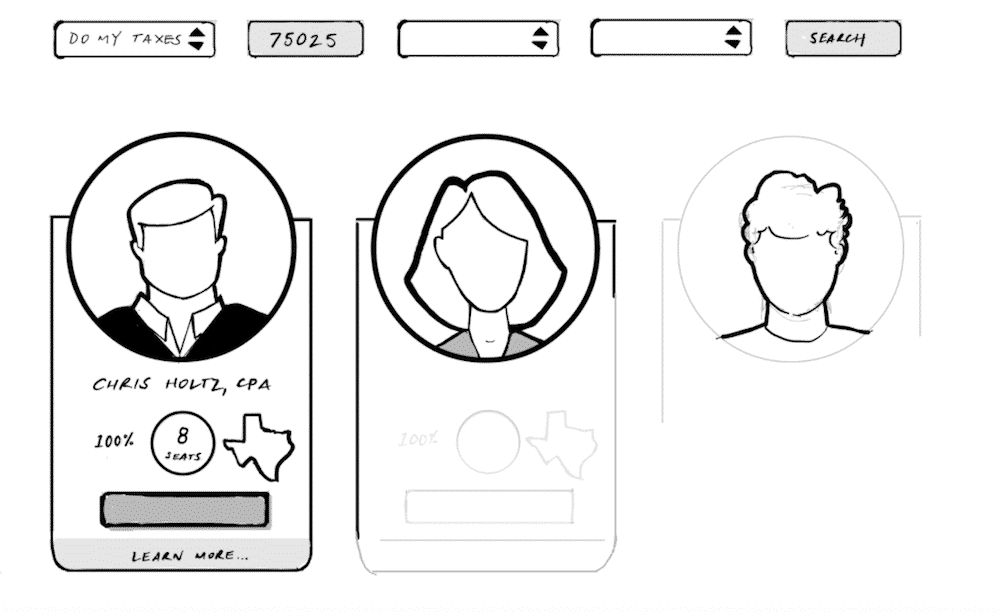

We solved big customer problems at Intuit — we built software to help consumers feel confident about doing their own taxes, for example. We were tackling that kind of customer challenge guided by a specific business model — working with great designers, and the best engineers. As a product manager being at the intersection of the customer, the technology, and the business, in my mind, was the closest thing to being a general manager.

A lot of people describe the product manager’s role as the “CEO of the Product”. What do you make of that moniker? What leadership challenges do you think product managers face?

BC: Leadership can be a hard thing to define. My prior CEO always said, “Your title makes you a manager, but the people decide whether or not you’re a leader.” I think that makes a lot of sense. Generally speaking, people want to be led. In product management, you lead by understanding customer pain (and advocating to solve it), driving towards the best idea, and then ultimately building that solution in a timely manner. Engineers, designers, and the team want to solve the problem, and at the end of the day, they are looking to be led.

Being a leader is not the same as being opinionated. It’s about the desire to “get it right,” not just “be right.” And while many people are working IN the business, it’s important as a leader to constantly working ON the business. These statements can be cliche, but they’ve always mattered to me. And the combination of the two is when we move from people working hard every day to working towards something that really matters — and is customer-driven, data-backed. Do that day after day, year after year, and the probabilities of success dramatically improve.

Tweet This:

“Being a leader is not the same as being opinionated. It’s about the desire to ‘get it right,’ not just ‘be right.'”

Being a leader isn’t something that just happens; it’s something that you develop over time and by experience — by succeeding and failing. It’s action-oriented. We follow people who have a vision, who make decisions, and who move.

What do you love about your job and what is the most challenging part?

BC: Earlier in my career, it was all about launching new products. And that was fun. But it was a new process for me and I didn’t have much confidence. Like anything, it’s been a maturation process. And so those first few times, it was so exciting just to get a feature released or to get a new product launched — and see customers using them.

I think it’s so true in every aspect of life. You get to a point where you can look back, reflect, and ask, “What was the best part of that experience?” There’s of course a big payoff when you launch something and people really love it, but if you didn’t enjoy the part where you were solving the problem — where you were working with customers, and poring over spreadsheets, and looking at data, and trying to synthesize it into insights (Eric Ries calls it “the photo montage”) — then you’re just not going to be a good product manager. If you don’t like that part, you should find a different gig.

I have much more confidence in the process — and a strong point of view on what that process entails. Today, I get just as much satisfaction seeing the members of my team develop as leaders as I do launching a new product. For the most part, my team is my product.

As far as the most challenging aspect of my job, I think it’s surprising how much of the job demands effective and efficient communication.

To be a successful product manager, you need to communicate not only what the vision is and what it is we’re building, but why we’re building it. Read Simon Sinek’s Start With Why. And because we’re agile and because we’re always changing, and constantly getting new data and insights, it becomes imperative that we bring stakeholders along. This often requires some kind of cadence or op mech within the company.

I use ProductPlan to help facilitate the communication of what we’re doing, when we’re doing it, and ultimately, why we’re doing it. As a cross-functional team, we review the roadmap together every month. In the earlier days of my career, I underappreciated the communication aspect of the job. But at the same time, if I had just done it effectively, I would have had an easier time — more time focused on building. I used to spend all my days managing stakeholders — and that’s not right. There’s a balance that needs to be struck, and we’re doing that here at Namely.

One of the first things I worked on when I got here at Namely was reimagining how we communicate both internally and externally. That involves getting different tools, different processes, and getting people aligned/trained on the new way. When it comes to customers, our communication also needs to be agile and contextual, and non-obtrusive. These are things that people don’t typically think about — they think product management is just about building products. But it’s so much more.

How do you manage conflicting priorities within your organization?

BC: There’s a three-part answer to this. First, teams need to operate under guiding principles — principles the organization is aligned to. For example, availability, compliance, security are usually the top of the list and are highly prioritized.

That sounds easy, but it can be difficult once you get past the “non-negotiables.” Soon after joining Namely, our CTO and I worked to get aligned with the other leaders on how we’d prioritize our backlog. It required aligning first on our product vision and strategy.

Apart from aligning on principles, it’s important to bring data to the discussion. The most ineffective meetings are those when decisions get made (or missed) because the loudest person in the room influences everyone else. Meanwhile, key insights and data points have the answer, or can at least aid a decision. For example, your data may show that users are dropping off at the top of the funnel, and nobody’s converting past the homepage, so why are you debating the user experience later on? What does it matter if there is no conversion? Good data and insights can open up the conversation and keep it objective.

And finally, when I say make customer-backed decisions, I mean bringing empathy back into the process and reminding people why we’re doing what we’re doing. I think that can also help unstick people when it comes to conflicting priorities.

It’s also really important to understand the role of escalation. If there is a debate amongst leadership, it’s ultimately up to the CEO to be the tie breaker. That’s a role our CEO plays and an example of how effective escalation can be. It isn’t always a democracy — the reality is we need to make decisions. I think understanding that is very healthy. Escalation is not a negative thing, it’s just about getting to decisions so that teams can commit to those decisions and focus on execution. Our CEO plays that role well here at Namely.

What tools or software can you not live without?

BC: I’ve learned to love a good whiteboard and marker. I have one on wheels, so I often take it with me. I’ve got one whiteboard out here in our working area, and I’ve got another one that sits right by my desk. I like whiteboards because ideas seem to flow when jotting them down. I do most of my writing there. I’ve still yet to find a good “digital whiteboard” for online collaboration. I know they exist, but nothing I’ve incorporated into my toolset.

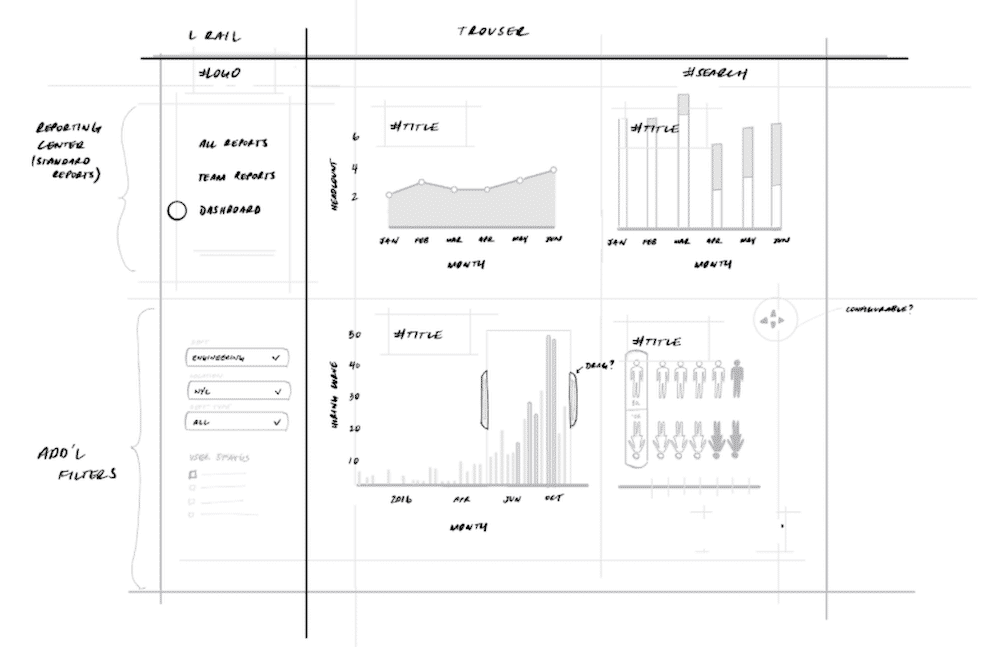

I also use Evernote, but mostly for sketching. I use Evernote + iPad to sketch out everything from new org charts to product sketches–to sketches of my presentations. I usually will sketch out my whole deck before I actually put it together (similar to building a product).

I view everything as a product — whether it’s a deck or whether it’s a team. The idea is that anything that’s early stage needs to be lower fidelity. I used to have a Moleskine notebook, but now that I have the iPad Pro, I mostly use that.

For example, I’ll sketch out a deck in Evernote, go over it with our CEO, and make real time edits without ever having committed anything to PowerPoint. That kind of rapid iteration process — going from low to increasing fidelity as I get more solid on the answer — that’s how I operate in every aspect of my life. Even my goals for next year are written in Evernote. Not typed, but written with my messy pen because it denotes the lower fidelity. Eventually, those goals will end up nice and typed out in Evernote, and then in our Namely platform.

I think all of these tools are pretty common for product managers; it’s how we use them differently that’s probably the more interesting. I’ve got four or five Trello boards, for instance. I use them for personal to-dos and admin to-dos in the business, and then I’ve got more strategic-level boards. I even have a family board where my kids actually have little things to work on. The high-level, Kanban format gives me a sense of understanding of what’s going on and what we’ve got coming up.

Describe your organization’s roadmap planning process. How far out do you plan?

BC: Like I mentioned earlier, the first step was getting everybody aligned on how we’re going to prioritize. Then we simply shared those prioritization principles with the team at an all-hands meeting, and talked through the high-level game plan and how we as the leadership team were aligned. Although it was very high level, there were decisions made. We were more explicit on what’s in/what’s out for this next year.

After we distributed the product vision and principles, the teams came back and shared their first draft of their roadmap. We pushed them a little bit on vision. We asked if it was aggressive enough. We made sure it was core to our platform, etc. The best part was seeing how collaboratively these teams worked across design, product, and engineering — and then collaborating with the rest of the business for feedback. It showed in the final result; the team’s roadmaps were very much in line with our strategy.

We focus on six months at a time, say 90% confidence for the stuff in Q1 and 60% confidence for Q2. In ProductPlan, I use milestones to show the beginning of the quarters, and on there, I actually write the percent level of confidence. This is our way of communicating with marketing for example to say, “Hey, this is what we’re going ship, but don’t take it to the bank.” Marketing would never look at Q2 features and communicate them to prospects in any way, but they at least know where we think we’re headed and they can give us feedback on it.

Tweet This:

“The worst thing is becoming beholden to a document that was wrong to begin with.”

It might be the case that we don’t ship what’s on the roadmap. I think the worst thing is becoming beholden to a document that was wrong to begin with just because that’s the nature of how we work. So that’s something we’re trying to break up. In years past, it was like, “Here’s the roadmap, and success for everybody means shipping everything on the roadmap.” But ultimately it’s about getting closer to solving our customer’s pain. That is how we are measuring success.

That’s our approach — and I think it’s pretty similar to how we did things at Intuit. I’m taking some of the best practices we had previously, but also realizing I can move even faster here at Namely.

How do you incorporate customer feedback into your roadmap?

BC: Here’s the thing. Usually, when customers give me feedback on stuff, I already know that it’s broken or that the user experience is bad. It’s either already on our roadmap, or it’s not because it just hasn’t hit the priority list yet. We have work constraints and limited resources, so everything on the roadmap has been prioritized, and there obviously has to be a cut line somewhere.

But the thing that steers the roadmap more than anything is customer insights. What I mean by customer insights is actually spending time with customers and observing how they use the product, and how they solve problems using a variety of tools — even what they do with paper.

Going onsite, in their office, and actually observing what customers are doing is so much more valuable than just listening to what they say.

If I’m on a phone call with somebody, I can’t see their environment. Let’s say I’m working on document management, and I’m talking to someone about how they use document management software. I’m listening and I’m thinking they’re probably paper-free, but then I go on-premise, and see they have all kinds of file cabinets. That leads me to my next step of discovery.

Having the contextual references and seeing their environment can lead to insights. When you watch them use your product, in their space, you see their stress — you see how they feel and you see the emotional side of it. Whereas on the phone they might just tell you, “Yeah, I use it. It’s a good product.”

What are some big mistakes that you’ve seen product managers make (or mistakes you’ve made yourself)?

BC: One mistake I made happened not too long ago, when we had just launched the French version of QuickBooks. During the setup experience, or the first time user experience, there was a period where the app would stall and spin for over a minute. It was a terrible user experience, and I remember coming onto that team and thinking, “Ugh, that’s not very good.”

But then I got caught up in the day job. Even though I knew it was not a good setup experience, I just accepted the status quo and focused elsewhere.

As a product manager, you need to be the person that advocates for good design and a good product, or nobody will.

Tweet This:

“As a PM, you need to be the person that advocates for good design and a good product, or nobody will.”

It took an embarrassing demo with a customer and a senior executive to bring it back to our attention. We all looked at each other and knew we could only blame ourselves for accepting the status quo. So that’s a trap that I’ve fallen into — and I’ve seen others fall into as well. At the end of the day, we need to be advocates. We need to advocate for the customer, and for great user experiences, and for great products. We need to always be raising the bar.

If you could give only one piece of advice to a new product manager, what would it be?

BC: We’ve talked a lot about making decisions and leading, but I think product managers who really excel are those who also find a way to build hand-in-hand with engineers and designers. We can be builders too.

Product managers should understand what it means to be a builder. That may mean learning to become more technical, or it may mean learning how to lead design thinking. It’s important to establish that role as you lead.

A PM who is more technical usually pulls their own SQL queries to better understand customer usage trends. In doing that, you’re gathering information that’s helpful to ensure you’re building and investing in the right areas.

Design thinking is the process of developing deep customer empathy and insight, and then building something that customers will love — and that’s being a builder as well. It’s not just about writing good user stories or setting a good vision. It’s about actually getting your hands dirty and building; sketching out designs, observing customers, sitting in on sales calls. This is the right step in the evolution of product management.

I would advise aspiring product managers to develop those skills. In your undergrad, learn how to code or learn how to design. Even if you ultimately want to become a product manager, you need to have technical chops — and you need to know how to actually build stuff.

You have been involved in bringing new products to market for quite some time. How has product management changed over the years?

BC: I think macro shifts used to happen every 3-5 years, but now they seem to be happening every six months — whether it’s the sharing economy or the gig economy. The world and its markets are changing faster. You look at all the newer companies that are driving the highest value, and they’re all network effects. Airbnb doesn’t own a single room. Uber doesn’t own a single car.

Even ProductPlan — you’re shifting from a feature-based approach to more of a platform. You now are spending more time building the pipes, because those pipes — and being at the center of those pipes — are actually much more valuable. You’re bringing much larger ecosystems together than if you just built a point solution.

This was a criteria I used when deciding which startup to join. I wanted to build a platform. And that is what we are doing at Namely. We have our core products, but we are becoming more of an open platform to connect 3rd party apps. It becomes a platform that is personalized to fit each of our client’s business needs. We are early in that journey, but are making great progress.